What is Zero Point Fixation?

In 2018, the ‘Zero Fixation Point’ policy was announced by the then French Interior Minister Gerard Collomb, to ensure that migrants do not have a settled camp in France. This policy has been in effect on the French coast for many years. This is real mental torture as it consists of regular expulsions of displaced individuals from their camps, every 36 or 48 hours in Calais and once a week in Grande-Synthe. Displaced persons are then obliged to take their tents, duvets, and other personal goods in time – at the risk of having them confiscated – and relocate further away in order to discourage them from staying or travelling to the United Kingdom.

To understand the legal and political importance of this policy, it is necessary to explain why a policy like this exists in the first place by looking at its historical context, how this policy happened, why this is a flaw in the French legal system and how this policy fits within a larger ‘immigration control’ project in France and even in the United Kingdom.

Why does the ‘Zero fixation point’ policy exist? – Historical Background.

The port city of Calais is a contentious and well-guarded bottleneck point for undercover passage to the United Kingdom and is representative of migration in France. Migrants began to arrive in greater numbers at this border in the early 2000s. The French Red Cross ran a reception centre in Sangatte from 1999 to 2002, through which an estimated 75,000 migrants passed. This centre was closed in 2002 because the British and French governments regarded it as a magnet for migrants, and people were forced to live in scattered villages in and around Calais. These were known as ‘jungles’: temporary encampments in wooded regions, amongst sand dunes, or on industrial wastelands. Living circumstances were despicable, and in the absence of government intervention, local citizens’ organisations organised food and clothing distribution.

The French government designated a place 5 kilometres from Calais city centre as a permitted space for informal camping in 2014, giving rise to the infamous ‘Calais Jungle,’ a dismal improvised camp that housed an estimated 8,000 people by the summer of 2016. The camp systemised the state’s ‘violent inaction’ towards migrants at the border, and their abandonment. The humanitarian system in the camp was built and sustained in significant part by informal actors: grassroots organisations that drew thousands of volunteer humanitarians who came to help in the settlement that lacked proper accommodation, sanitation, and infrastructure. By the summer of 2015, conditions had deteriorated to the point where Médecins du Monde (an international humanitarian organisation) decided to deploy its emergency response programme on French soil, in collaboration with the NGOs Secours Catholique Caritas France, Secours Islamique France, and Solidarités International (Secours Catholique Caritas France 2015).

Following international outcry about the camp, the French government demolished it in October 2016 and relocated residents to the Centers d’accueil et Orientation [Welcome and Orientation Centre]. These people were assured that the Dublin Rules would not apply to their cases and that their asylum applications would be processed in France. But this one-off solution, which was only partially implemented, did not solve Calais’s underlying problem, where newcomers are constantly arriving. These groups were either determined to reach the UK or aware of the threat of relocation to the first EU member state under the Dublin Regulation. A policy known as the “zero fixation point” was implemented following the camp’s demolition: There will be no more camps at the border. This was enforced by regularly detecting and eliminating informal encampments through extensive police operations. This action was justified by the existence of the state’s accommodation system (A free-housing system for displaced people in France), but it didn’t consider the legitimate fears of removal to the first country of entry of those who didn’t choose this protection. Humanitarian efforts were undermined, migrant people were criminalised, and the state asylum system was portrayed as resentful. Calais became a vivid illustration of how the Dublin regulation could hinder some asylum seekers’ access to the institutions and services they were entitled to.

How is the ‘Zero Fixation Point’ Fulfilled?

This policy is fulfilled through the police and border authorities with the acquiescence (passive acceptance) of the judicial and local executive powers. Over the years, heavy security and monitoring infrastructure has been erected to limit displaced people’s access to ports and train terminals as well as prospective habitation areas including woodlands, industrial areas, and abandoned buildings. Police officers are used for the eviction and destruction of migrant camps located a short distance from the city centre of Calais. They do this by using tear gas, rubber bullets and water cannons to forcibly evict the migrants. Human Rights observers – an independent watchdog have also witnessed French authorities urinating on people’s belongings. As a result, displaced people are obliged to take their personal belongings before they are confiscated and relocated further away, or hide in a place with the worst living conditions.

Other displaced people who linger in the camp either out of exhaustion or in rare instances of carelessness are swiftly removed. It didn’t appear to matter much to the police that some of these displaced people may have been asleep or making breakfast when the violent dispersal interrupted them. They seize and destroy many of their goods, including tents, mattresses, and other necessities. Thus, the camp previously housed by hundreds of displaced people, is again vacant with some sleeping bags and jackets covered in frost —shortly to be burned by the authorities.

The authorities carrying out mass evictions do not effectively take specific steps to protect unaccompanied children. A Kurdish woman from Iraq told Human Rights Watch in December 2020.

“When the police arrive, we have five minutes to get out of the tent before they destroy everything. It is not possible for five people, including young children, to get dressed in five minutes in a tent.”

It is particularly shameful that over 650 children have been living in the jungle in these conditions, many for months on end. The lack of proper child protection measures in place increases the number of broken families for relatives who are unable to reunite because of this policy.

It may be French authorities who assault the refugees; however, they have the financial and operational support of the French and British states.[1] The French government receives batons and bullets from the UK government. In 2021, the UK paid £55m for French border patrols to crack down on border crossings; the money is used to install barbed wire, CCTV, and detection technology. By paying France to criminalise the displaced people, the UK attempted to absolve itself of any international or moral obligations toward refugees.

How is ‘Zero Fixation Point’ policy flaw in the French system?

To understand how and why ’Zero-point fixation’ is a flaw of the French system is important to know the impact of this policy on displaced people or migrants. And enquire if it fulfils its aims.

The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) compiles data on refugee camps all over the world, but the Calais “Jungle” is regarded as being unofficial, and no information is gathered about it. According to the research, those living in the camp are “incredibly vulnerable” because there is a lack of information; a significant majority of them are unaccompanied children.

Some have referred to the phrase “forever temporary,” to describe the situation in the north of France, emphasising how absurd it is for something to be both temporary and permanent at the same time. This is due to the recurrent destruction and resurgence of settlements of displaced people. There is a constant cycle of dislocations, returns, inflows and outflow of displaced persons with the transit point being used as a yardstick to define the situation. However, the policy’s desired effect to hinder people from entering or leaving Northern France is ineffective. It only worsens the living conditions and restricts access to the protection of numerous displaced people who continue to enter the area despite the government’s strategy. As stated by Tarsis Brito, the Zero fixation point policy in Calais, simply,

‘does not direct migrants to another migrant camp. Their eviction does not represent a moment of closure that will redirect them to a secluded area wherein migrants should remain Migrants are endlessly dispersed, put in motion; denied the possibility of “remaining”, “possessing”, or “belonging” somewhere, even if for a short period of time. There is no promised space, no foreseeable “grounded future”.

According to Human Rights Observers (HRO), a group that frequently observes police evictions of these encampments, police carried out more than 950 routine eviction operations in Calais and at least 90 routine evictions in Grande-Synthe in 2020, seizing nearly 5,000 tents and tarps as well as hundreds of sleeping bags and blankets. These strategies keep both parents and children on high alert and preoccupied with surviving each day. Many people are tired, drowsy, and, as the French Defender of Rights, the country’s national Ombudsperson, noted in September 2020, “in a state of physical and mental exhaustion.”

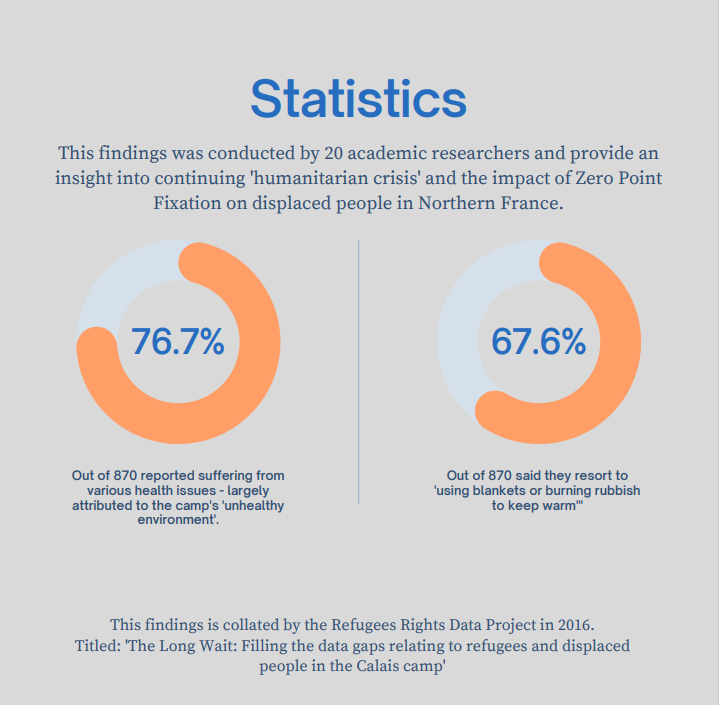

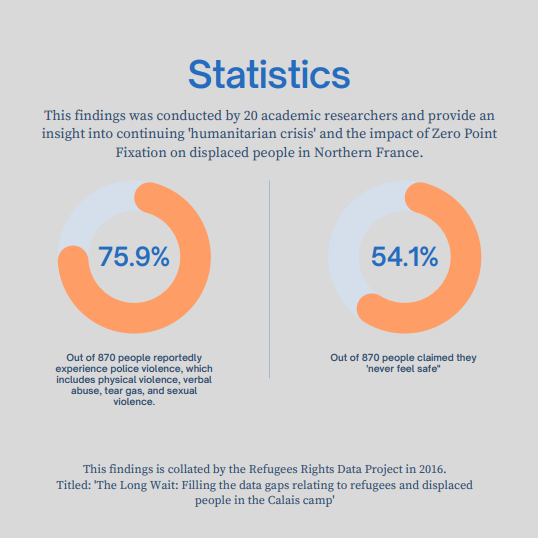

Statistics

This also pushes some migrants to the brink of death, as shown by the case of a young man found dead in Marck near Calais last May 2022, hanging from a strap in a trailer. In addition to these traumas, this tactic fosters a climate of distrust that hastens the dispersal of camps along much of the French coast and inland. “Calais is the tip of the iceberg.” one activist points out.

To conclude Zero does not seem to fulfil its aims. Police efforts to evict adult and child migrants from Calais and Grande-Synthe have not deterred new arrivals. There is no decline in irregular channel crossings. But police practices are causing more pain for migrants. It is shocking that vulnerable people escaping terror, conflict and persecution arrive in the safety of Europe only to face further human rights abuses.

How does this policy fit within a larger ‘immigration control’ project in France and in the United Kingdom.

The governments are trying out increasingly harsh methods to dissuade and prevent ‘undesirable’ migration onto State territory. The UK government decided to experiment with sovereign border control beyond its own territory. Since the 1990’s it has gradually exported and outsourced its border into French territory through a set of bilateral agreements known as ‘Juxtaposed controls’. Thus, allowing British immigration to extend to the French coast and then to the interior of Brussels and Paris. These Juxtaposed controls, such as the ‘zero fixation point’ and agreements have made the Northern French coast a ‘buffer zone’ with a tripartite immigration control strategy – prevention, dissuasion, and removal. Presented as needed for ‘border security’ and ‘crime prevention’.

However, in reality, they are the catalyst for the lack of safety and insecurity for hundreds of displaced people in France. They serve to create a harshly enforced zone of ‘deterrence’ acting as a precursor to the UK’s own domestic ‘Hostile Environment policy.

Relatively little attention has been paid to UK border ‘exports’ to France, despite the growing academic interest in the impact of externalised border controls in recent years. Parallel administrations over British and French territories were established through a series of bilateral legal agreements. As a result, potential asylum seekers were stranded on the northern French coast, subjected to highly unpleasant living conditions and systemic violence, and denied entry into the UK asylum process.