Understanding the crime of solidarity

Around the world, an increasing number of people are subjected to criminal charges for assisting displaced people, particularly those seeking refuge. Simple acts such as leaving water in the desert, saving someone from drowning in the sea, and providing someone with a lift to a medical facility or a bed for the night can result in arrest and imprisonment.

The crime of Solidarity, also known as the ‘delit de solidarité,’ is an example of legislation employed in France to punish those who assist a foreigner. To understand the crime of solidarity in France, it is important to unfold what problem the solidarity offence poses to society and why it is so publicised in the French context. But first, how is ‘delit de solidarité’ and its exemption defined in French Legislation?

‘Any person who directly or indirectly assists or attempts to assist the entry, movement or residence of an irregular non-national in France is to be punished,’ under Article L.622.1 of the Code of Entry and Residence of Foreigners and Right of Asylum (CESEDA). Thus , helping, facilitating, or attempting to facilitate a foreigner’s illegal entry, movement or stay is a crime.

However, this does not apply in three situations according to Article L.622.4 of the CESDA, where (i) the person has family ties, such as, parent, siblings or child to the displaced person; (ii) the person has a marital ties with the displaced person; (iii) the action has been done to ensure dignified and decent living conditions of the displaced person, by providing legal advices or provision of food, or accommodation. Or other assistance to preserve the dignity or the health and well-being of the displaced individual, providing that this assistance does not give rise to any direct or indirect compensation.

Charges for this offence can be cumulative and the maximum punishment the court can impose is a fine of € 30,000- and 5 years imprisonment. This means the court can impose lesser sentences, including suspended sentences according to their discretion. And if the court considers that the offence has not been committed or the person prosecuted must benefit from the exemption provided by the law, they can release the persecuted person. As they have the autonomy to convict a person, without giving any penalty.

What is the problem with the Solidarity offence?

The Article does not provide enough protection against those being prosecuted on a humanitarian and selfless basis. A selfless act can be described as without compensation or reward. However, this might be used to discourage or intimidate a person with an ‘entirely altruistic goal’ for two main reasons.

First, exemptions provided for in Article L. 622-4 do not apply to the offence in relation to the entry or transit. Even though it was done in a selfless manner and without receiving any compensation. It only applies to the assistance to the unauthorised residence of an undocumented displaced person.

This means a person can be prosecuted and charged if they helped a foreigner cross the border or even only helped them go from one place to another within the French territory, for example, by driving them.

The abuse of this exemption is seen when a volunteer helped a displaced pregnant lady, who is having a contraction to the hospital. Instead of being seen as a hero, he was arrested for helping them. And faces a charge of five years in prison and a €30,000 fine.

Details

Secondly, exemptions are limited even in a situation of helping to reside an undocumented displaced individual illegally, the part where the ‘crime of solidarity’ exemption applies.

The exemptions are fairly simple, as they have to belong to the family of the assisted foreign national to avoid prosecution. However, this gets more complicated when the person assisting is not part of the foreign national family. Surely, any person who is not a relative, but whose alleged act does not give rise to any direct or indirect compensation, and provides legal advice, provision of food, accommodation, or medical care to ensure dignified and decent living conditions of foreigners, or any other assistance to preserve the dignity or the health and well-being of foreigners benefit from the exemption. (CESEDA, Art. L. 622-4,3).

But this part of the exemption is devious and trickier than it seems for two reasons.

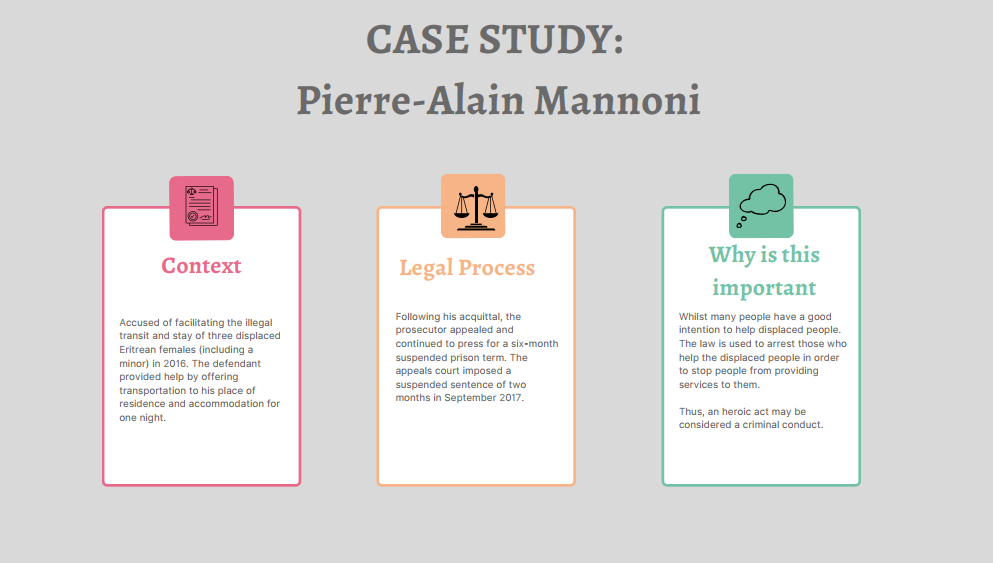

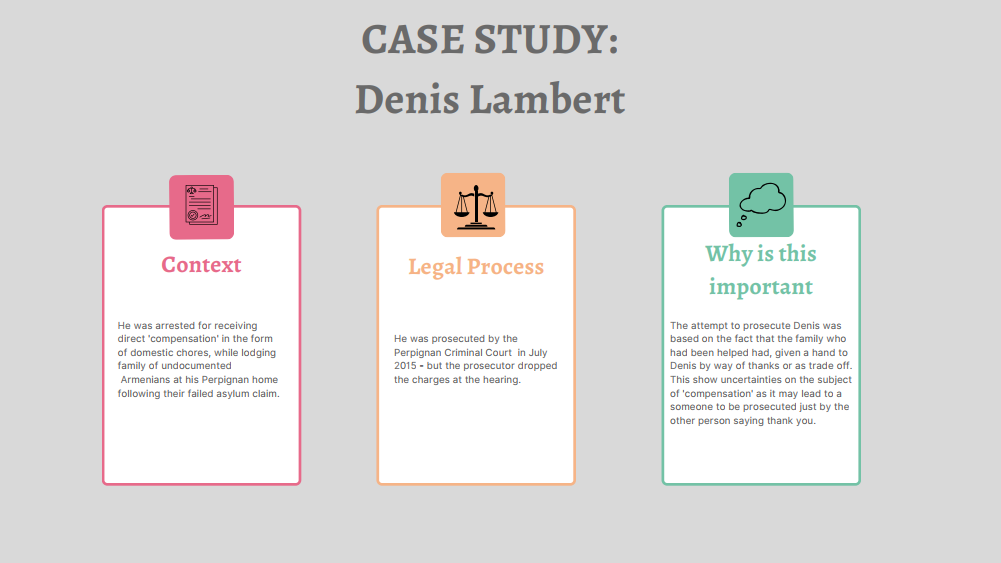

- The helper must not receive any direct or indirect compensation.

There is no clear definition of what compensation would or should be. Is this a monetary compensation or word of affirmation, such as thank you, or the feeling of good for helping a person out? This has led to uncertainties in some situations, and there are multiple attempts to prosecute people because a person who had been helped had made a hand gesture to their helper by way of thanks or as a trade-off. This happened in July 2015 when the defendant was prosecuted by the Perpignan Criminal Court. They had provided shelter for almost two years to a family that had participated in the household duties, such as cooking, and housekeeping for them, but the charge was dropped. As it must be proven to the court that there is an existence of compensation.

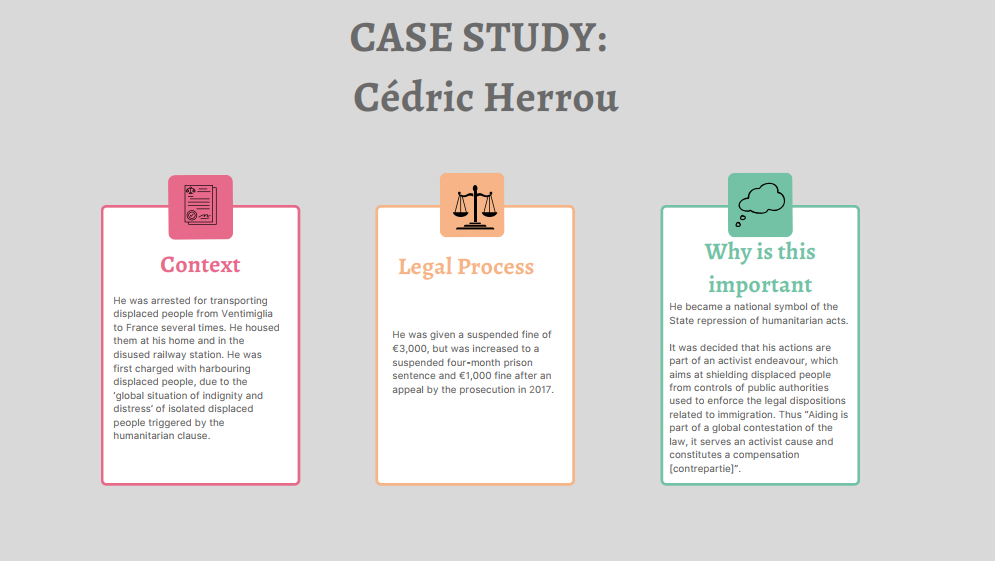

In this situation, a person could be called a hypocrite for their charitable activities. This is because by helping, giving, welcoming and comforting foreigners who may be depleted and disoriented in a new foreign land, may result in them having a ‘warm-glow’ or ‘Valmont effect’. Similarly, the most famous case of Cédric Herrou in the Roya Valley between France and Italy.

This is particularly troublesome from a normative standpoint because it indicates that a compensation does not only include tangible compensations (money, products, or services), but also moral ones. It appears that gaining symbolically from an act of hospitality may make the act less selfless and thus less humane.

2. Certain conditions must be met even when the assistance was given without compensation.

In circumstances where food provision, lodging services, or medical care, is provided, it must be with the ‘intention to ensure decent and dignified living conditions for the displaced people.’ If legal advice was given, there is no need for further conditions to be satisfied. Any form of assistance that does not match the criteria mentioned as if it was any other assistance, must be to ‘uphold the dignity and physical integrity’ of the assisted person.

However, this condition is difficult to meet. For instance, what if the person helped to charge the foreign non-national cell phone, or teach them how to read and write in French for communication, which is needed in a French country? This is not considered an act to ‘uphold the dignity and physical integrity’ of the assisted person. Thus, the person assisting can be punished by the law even if those acts are selfless and there is no compensation or reward. The Constitution Court in France had tried to ratify the measures of criminalising the facilitation of authorised entry and residence, in situations where the law does not allow exemptions to people who acted for humanitarian purposes.

Is the ‘crime of solidarity’ compatible with European texts?

European Directive 2002/90 defines the ‘facilitation of unauthorised entry, transit and residence’ and states the appropriate sanctions each Member State should adopt. First, to any person who intentionally assists a person who is not a national of the Member State to enter, or transit across, the territory of a Member State in breach of the laws of the State concerned on the displaced people; and secondly, to any person who, for financial gain, intentionally assists a person who is not a national of a Member State to reside within the territory of Member State in breach of the laws of the State concerned on the residence of displaced people.

The French legislation goes way beyond this Directive. The directive distinguishes between the facilitation of illegal entry and transit, which can both be punished, even if the helper does it with the intention of not being compensated. And the assistance to residence, which is punishable by Member State only when the person has the intention to make profits. Especially, when they help and are expecting retribution as a reward for the help provided. However, in France, people can be prosecuted for various forms of assistance to foreigners without a profit-making purpose as already mentioned.

It is obvious that the French government adopts a much broader definition of the facilitation of unauthorised residence than the one adopted by the EU. To tighten the law on the criminalisation of solidarity, and have the freedom of using this broad definition to arrest or condemn people showing solidarity. They ignored the ‘profit-making purpose’ aspect, the key element of the directive, and refused to include a humanitarian clause that makes it impossible to impose penalties if help was provided for humanitarian reasons to displaced people. Thus, the legislation, which is supposed to align the concerns of citizens and organisations providing practical aid to undocumented displaced people, supports the notion that unselfish aid given to an illegal migrant is punishable by the law.

This is similar in Belgium where a person who helps a person who is not citizens of a Member states of European Union to reside will be punished, but this punishment can be negated if the assistance was provided for humanitarian reasons, unlike the French law.

The crime of solidarity: Égalité, Fraternité, Solidarité

In 2018, the French Constitutional Council ruled the crime of solidarity was partially unconstitutional, as it was not in line with the principle of ‘fraternité’. This principle is important to the French because it is suggestive of the importance of French people seeing themselves as being together in struggle, united by their beliefs and nationality, since the French revolution. Thus, the constitutional principle of fraternity protects the freedom to help others for humanitarian purposes, without even considering their legal right to reside on French territory. This then allows people helping with the circulation of displaced people, whatever their status and the legality of their residence to be protected, but facilitating entry on the territory is still forbidden. And while helping had only been permitted if done to protect the dignity and physical integrity of a displaced individual, the Council believed now that fraternity should be interpreted in accordance with any act of help done for humanitarian goals.

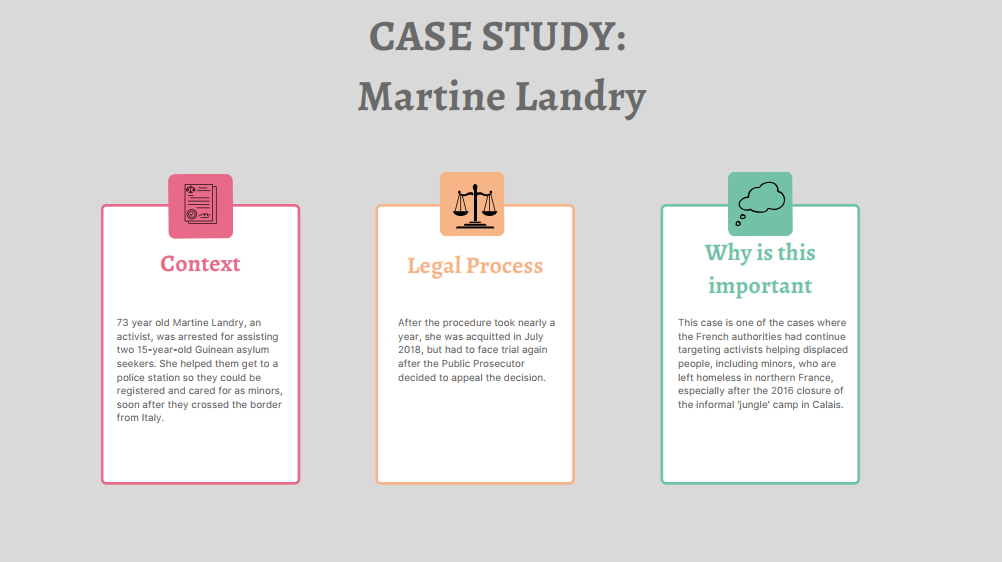

However, despite the unconstitutional ruling from the council court, the French authorities continue to target activists helping displaced people who are left homeless after the closure of the informal Jungle camp in Calais. This indicates deeply there is a crime of solidarity in France.